Note: this post contains information about residential schools and genocide that may be triggering to some readers.

I once had a linguistics teacher who said: “the only thing that matters in the act of communication is that the message you want to convey gets passed to the intended audience.” As a university student who spent her entire academic career in the Canadian system, it had been a revelation. It makes a lot of sense—when we speak and write to each other, the goal is always just to have our audience understand what we’re trying to convey—but to a person who had been taught that such things as ‘proper’ grammar and spelling existed, it was hard to wrap my head around.

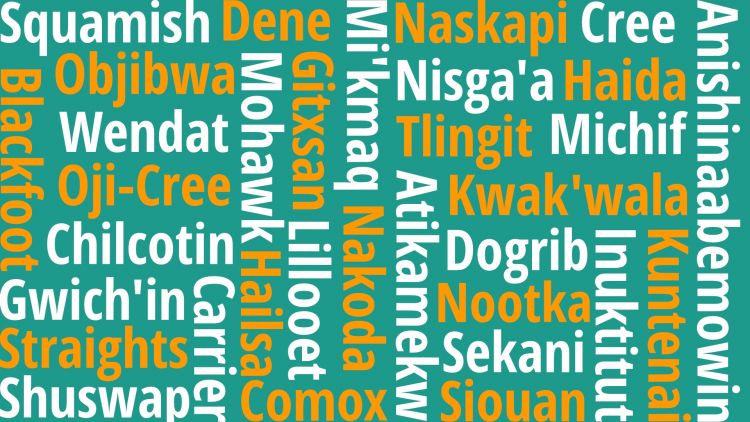

That semester, I learned that language is a constantly evolving push-and-pull: language can be used as a colonizing and classist tool meant to perpetuate white supremacy and racism, alongside its ability to act as a de-colonizing and freeing force. Though it’s a tool, it is also how we connect and relate to the world around us. Language has tremendous power. So, for the UN’s decade of action for Indigenous languages, GreenLearning is celebrating the languages that have made up the land we call Canada since time immemorial.

Indigenous Languages and Colonial History

It’s no secret that Canada has committed genocide against Indigenous Peoples. Residential schools played a large part in modern assimilation tactics; these religious Western boarding schools were opened for the sole purpose of completely stripping each student of their Indigenous identity. As culture and language are inextricable, Indigenous languages were banned from being used in schools, along with Indigenous names. The fact that some students spoke no colonial language didn’t matter: punishment for speaking an Indigenous language ranged from isolation and starvation to outright violence. As a result, many residential school Survivors either lost their language or refused to pass it on for fear of putting themselves and their children in danger.

According to Canadian Geographic (2019), of the 60 or more Indigenous languages that still exist in Canada, only Cree, Inuktitut and Ojibwa are stable, with most of the linguistic diversity occurring in British Columbia: 30 languages with fewer than 1,000 speakers, each. Though not all are in danger of disappearing—90-97 percent of folks who speak Atikamekw, Innu, Oji-Cree, Dene and Inuktitut, speak it regularly and at home, despite not being in necessarily huge numbers.

Indigenous language—whether it be in Canada or abroad—is always rooted in cultural context, which means it’s also rooted to place. In Inuktitut, Iqaluit means “place of many fish”. Conversely, settler languages carry legacies of imperialism and colonialism. As Europeans drew maps of places they had supposedly discovered, colonial place names—which had no real connection to the land or its inhabitants—were forcibly adopted. This “disembodiment” of language creates a disconnect between ourselves and the land, making it all too easy to build pipelines and log forests. In English, the mere fact that we use words like ‘ownership’ and ‘rights’ when referring to land changes the way we interact with it. We are not caretakers with a responsibility, but owners. This strips us of all accountability, to say nothing of its inherent individualism. Conversely, in Anishinaabemowen—the language of the Anishinaabe people—there is no such word for ‘rights’; instead, the closest translation would be “a duty and responsibility for community survival”. If language is culture, the difference here is clear—and important.

Language is Land, Land is Language

“Indigenous languages are like ecological encyclopedias and ancestral guides with profound knowledge cultivated over centuries. If these languages are not passed on, then this wisdom is lost to humanity and the generations to come.”

—Pòl Miadhachàin (Paul J. Meighan)

Indigenous culture is not a monolith, but there are certain incredible ways of life that are universally attributable to Indigenous Peoples, such as their strong connection to land, and the connection between their lands and languages. Similarly, land and language don’t exist in a vacuum. To think of just the connection between the two would be a vast oversimplification of how land and people interact with one another. Aliana Violet Peter describes this as a matrix that has four main pillars: language, ceremonial cycle, sacred history and place/territory. These pillars are interconnected, resulting in a worldview that prioritizes respect for land and community—and land-as-community—over all else. So when we celebrate Indigenous languages, truly, we’re celebrating Indigenous worldviews, ways of being, and culture. There is no one without the other.

For example: Kwak̓wala is the language of the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw people, who live on the mid-coast of British Columbia. According to native speaker Andrea Lyall, Kwak̓wala “expresses a connection to the land through words, stories, and ceremonies, which describe the patterns of the seasons, traditional use, important places, and cultural and spiritual values.” Lyall explains that Kwak̓wala describes how the forest functions: plants and places are named for their appearance and function—the English translation of a’agala, a small and rare plant containing wintergreen, is “it grows in the shade.” Looking more deeply into the linguistics of a word can also reveal how that plant/animal/place was significant to trade and interactions among communities and Nations, in addition to spiritual and ceremonial significance. “To Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw,” Lyall explains, “plants and animals are more than things: they hold spirits, and some plants and places are considered supernatural and important spiritually for our ceremonies.”

The number of words to describe a single entity is also significant. If a plant is not of use to the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw (for food, medicine, ceremonial purposes, etc.) then it’s not given a name. Conversely, there are at least 41 words to describe the Western red cedar in Kwak̓wala. This vocabulary ranges from the parts of the tree to its uses. Furthermore, language is essential to passing on the stories and songs that hold Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw history, traditional practices and foods, such as “the importance of women cultivating clam gardens, shamans picking medicines, relationships with the animal kingdom, and sharing of wild salmon and seafood.” Kwak̓wala is therefore not only the language of the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw, but a roadmap to understanding how to work with the ecology and ecosystems of their land.

How would our lives change if we referred to plants, animals and places by their Indigenous names? If we taught the next generation the importance of the land through language that doubles as a historical archive? Could you imagine not only learning the name of a place or thing, but its significance and history to humans and the environment? Because Indigenous languages are so place-conscious, a focus on language when teaching about the environment could go a long way in changing learners’ perspectives on how they exist in relation to where and how they live.

Moving Forward

While knowing the importance of Indigenous languages—to culture, worldview, environment and to reconciliation efforts—is a good first step, incorporating that knowledge into lesson plans is even better! We’ve put together a short list of some great resources that our team has found helpful.

Native-land.ca is a community-led project that maps the general lands of various Indigenous Peoples around the world.

Google Earth has created an interactive map of Indigenous people sharing their languages. The map is currently incomplete, but it’s international and presents a great summary of the importance of the language to the speaker, a handful of recorded phrases, and a pronunciation guide.

This TEDx talk by Lindsay Morcom, which talks about the history of Indigenous languages and how to revitalize them.

Can Geo Education put together this really awesome website and map about Indigenous place names in arctic lands

The colonial violence inflicted upon Indigenous identity has resulted in trauma that requires a culture of care; while enthusiasm is important, teaching any material that has to do with Indigenous language and culture must be done with context in mind. Perhaps the best place to start supporting language revitalization is by learning which People(s) originally inhabited the land where you live, work and play, and which language(s) were (and/or still are) spoken. Are there any teachers you can learn from? Any local revitalization efforts you can support? Start by learning about the history of the land you are on, reaching out to Indigenous Peoples around you, and listening to and amplifying their stories.

As part of its reconciliation efforts, the government of the land we call Canada has highlighted language revitalization. For more on the policy, as well as social media toolkits to help support Indigenous language revitalization and resources to aid in revitalization, see the Assembly of First Nations’ website.

Topics: Indigenous language, Environmental Justice, Environment, Residential Schools

Back to Blog